As a mariner, having a solid grasp of navigational tools and instruments is a fundamental necessity!

These equipment are the backbone of safe and efficient navigation at sea because, without them, our merchant ships can never set sail safely to any port.

Whether piloting a massive container ship or a modest barge, accurate navigation can mean the difference between a safe voyage and a disaster.

This article will provide an overview of the most critical marine navigational tools, explaining their essential functions and importance on board ships.

Key Takeaways

- Navigational tools serve as the cornerstone for ensuring the safety and efficiency of ship movements.

- Radar, ARPA, AIS, and ECDIS provide enhanced situational awareness and collision avoidance.

- Traditional equipment like the magnetic compass and sextants are still critical backups for when advanced systems fail.

- The integration of multiple tools listed below forms a holistic approach to navigation. This ensures a comprehensive understanding of the vessel’s surroundings, contributing to safer maritime journeys.

What are navigational tools?

Marine navigational tools are instruments and technologies seafarers use to determine the ship’s position, plot their course, and avoid hazards while at sea.

These tools are essential for safe navigation, avoiding collisions, and ensuring the overall efficiency of maritime operations.

They encompass a range of both traditional and modern devices, each serving a specific purpose in guiding ships through various waterways.

25 Marine Navigational Tools You Can Find on the Ship’s Bridge

While your eyes and ears can only function with limited potential, these navigational devices extend the capabilities of seafarers by providing accurate and real-time information.

Here are 25 marine navigational equipment you can find on board and a description of their functions.

We all know these are all critical. But I’m still arranging them based on their overall impact and indispensability in modern maritime navigation.

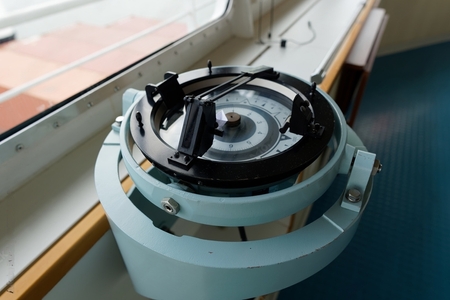

1. Gyro Compass

A gyro compass is an electrically powered compass that provides accurate and reliable heading information.

Due to its fast-spinning gyroscope, unaffected by external forces like magnetic fields or ship movement, it always points to true North.

This device is crucial for accurate and reliable direction, especially during course-plotting, extended journeys, and integrating with other systems like autopilots.

The gyro compass is located at the centerline inside the ship’s navigational bridge, with repeaters on the port and starboard wings.

2. Magnetic Compass

A traditional navigational tool consisting of a magnetized needle that can rotate freely and align with Earth’s magnetic poles.

A magnetic compass works by providing a stable heading reference for direction and visual piloting. By utilizing the earth’s magnetism, this compass is independent of power supply but requires swinging/adjustment to correct for shipboard deviations.

While traditional, it remains a steadfast companion and acts as a crucial backup in case of electronic failures.

3. Marine Radars

Short for RAdio Detection And Ranging, this equipment is your eyes, especially during nighttime and low visibility.

A Radar detects objects in poor visibility conditions, including other vessels and landmasses, which is vital for avoiding collisions.

A marine radar utilizes electromagnetic radio wave pulses and aerials to detect the range, bearing, and speed of surrounding objects. It also comes in two types: an S-Band and an X-Band Radar.

This tool provides a comprehensive picture of the ship’s surroundings by “printing” the radio waves on a Plan position indicator or PPI.

4. Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA)

An ARPA enhances the capability of the Radar. It is a Radar feature that can automatically acquire and track targets within defined acquisition zones.

Some of ARPA’s functions is to automatically provide additional information about tracked targets like their heading, speed, CPA, TCPA, etc.

These data are important for improved decision-making and collision avoidance

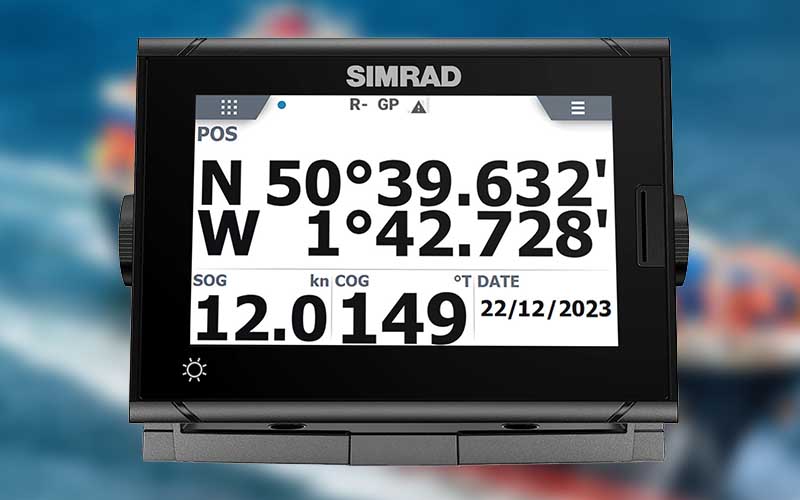

5. GPS Receivers

The Global Navigation Satellite System triangulates signals from orbital satellites to determine a vessel’s precise real-time latitude, longitude, course, and speed.

Global Positioning System enables accurate worldwide navigation and position-fixing when used with modern chart plotting.

Vessel tracking websites also use GPS technology to track ship movements worldwide.

6. Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS)

ECDIS is the successor of our traditional paper charts or a digitized version. Think of ECDIS as the “Google Maps for seafarers” but packs more informational punches.

An ECDIS is an electronic chart that provides real-time navigation data to the mariner. It integrates GPS positioning, Gyro Compass, ARPA features, AIS, an echo sounder, a speed log, and many other bridge equipment.

These integrations facilitate route planning, monitoring, and alarm management making them crucial for safe and efficient navigation.

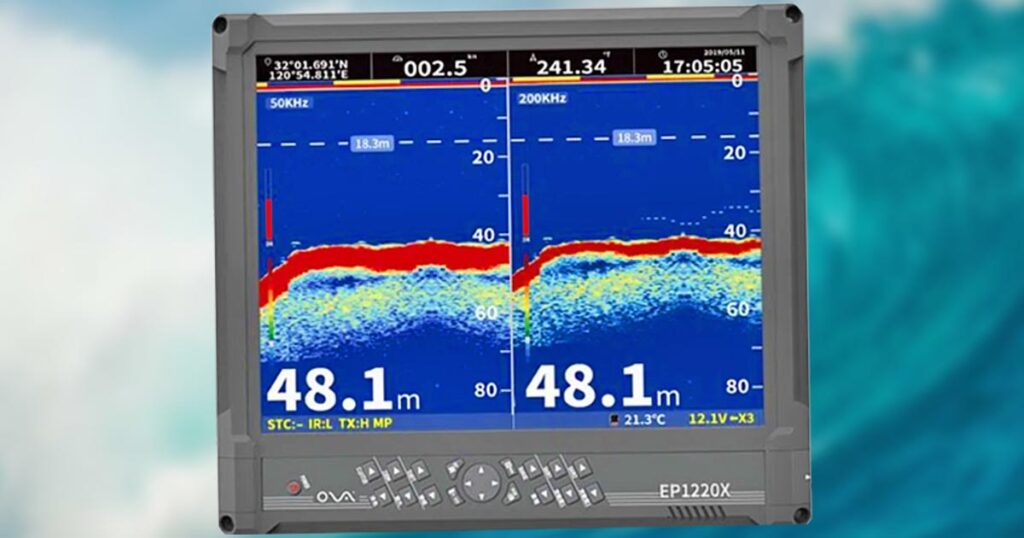

7. Echo Sounder

An echo sounder is a sonar device that emits sound pulses and then measures and displays the seabed depth beneath a vessel by timing the return echo.

Echo sounders are useful for marine navigation. As our only “eyes” underwater, an echo sounder aids in preventing grounding and ensuring safe passage through varying depths in unfamiliar waters.

Some can even show the bottom composition.

8. Automatic Identification System (AIS)

An AIS is a device that broadcasts and receives identification information from other vessels or shore stations, enhancing situational awareness and avoiding collisions.

This ship identification equipment integrates with other navigational tools inside the bridge improving safety of navigation, especially in congested waters. You can even send a short message to other stations using the AIS.

Information that a vessel’s AIS sends out and receives are the following:

- Vessel Name

- Callsign

- MMS

- Position

- Course

- Rate of Turn

- Cargo type

- Draft

- Destination

- ETA

- Navigation Status, etc.

9. Long Range Tracking and Identification (LRIT)

An LRIT is a satellite-based global vessel tracking system that provides periodic position report transmissions to maritime authorities.

It is used for long-range tracking and identification of vessels, contributing to overall maritime security and surveillance purposes while supporting search and rescue efforts.

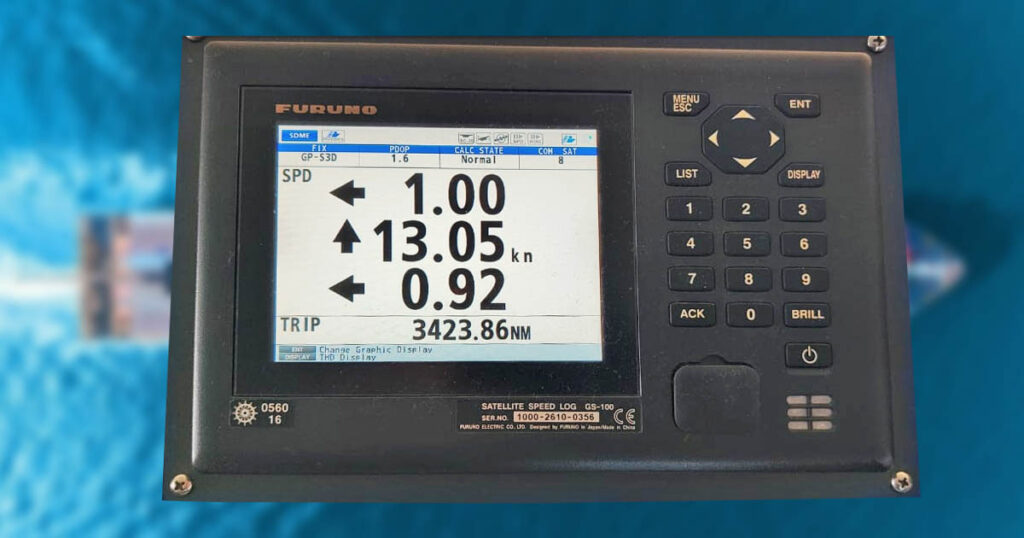

10. Speed and Distance Log Device

This instrument provides crucial information about the vessel’s speed and distance traveled.

These essential navigational inputs are crucial for voyage planning and monitoring progress, as well as for ETA, fuel consumption, and avoiding ocean currents.

Interested why we call the ship’s speedometer a log? Here’s a post about the origin of ship terminologies.

11. Autopilot System

The autopilot system automatically controls the heading and course by adjusting the rudder position.

I like calling this tool the helmsman’s best friend since it relieves him of the tedious task of steering.

The autopilot system interfaces with heading sensors and other navigation systems to steer pre-programmed routes or maintain set courses with minimal human supervision, reducing workload.

Because it alleviates the crew for manual steering, this navigational tool is helpful during long passages, allowing navigators to focus on other critical tasks.

12. Rudder Angle Indicator

Displays the angle of the ship’s rudder relative to the centerline. It indicates rudder/steering system response and allows anticipation of turning effects on the vessel.

Rudder angles usually have increments of 10 degrees and a maximum angle of 60 degrees, depending on the rudder type. It is also color-coded with red for the port rudder and green for the starboard.

It is helpful for course keeping, course alteration, and piloting, where the vessel frequently changes its course.

This is also a valuable tool for helmsmen who are steering the vessel.

13. Rate of Turn Indicator

Also called a RoT indicator, this device measures the rate at which the vessel is turning.

The Rate of Turn Indicator can be an analog or digital instrument usually installed close to the steering wheel. This indicator is particularly useful in assessing how fast the vessel is turning when changing course, especially during restricted visibility.

One of its best uses is to preset your autopilot system to use a maximum turn rate when altering the vessel’s course.

Setting up your Rate of turn is also essential in finding your wheel over position when approaching the next waypoint.

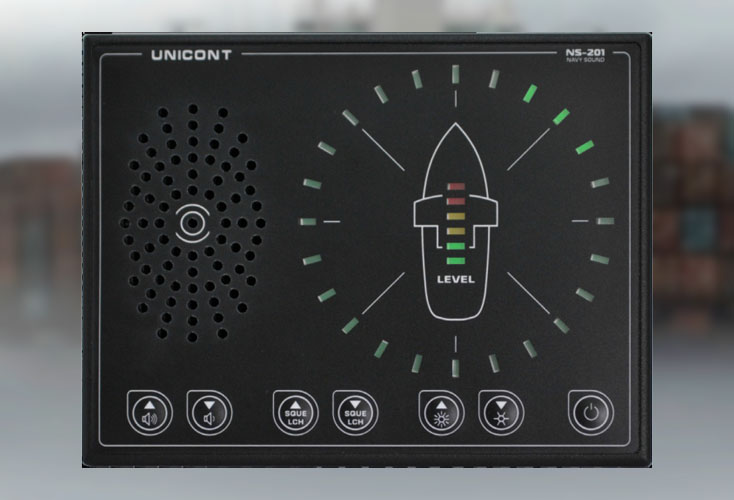

14. Sound Reception System

Years ago, whenever we had restricted visibility, it was a standard operating procedure for our captain to open all the bridges’ doors so we could hear fog signals.

But with a fully enclosed bridge, this was not possible.

Hence, installing the Sound Reception System became the solution so the navigating officer could hear fog signals for a fully enclosed bridge.

15. GMDSS Console (Global Maritime Distress and Safety System)

A GMDSS is a vital communication tool that ensures connectivity and distress alerting in emergencies.

It integrates DSC VHF, NAVTEX receivers, satellite terminals, and MF/HF radios to facilitate maritime distress alerting and routine communication.

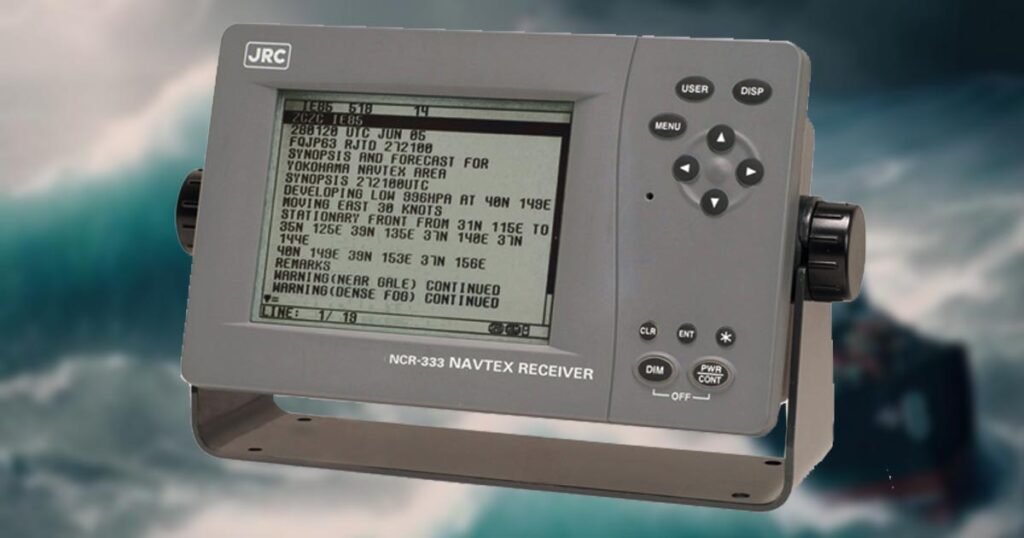

16. NavTex

A NavTex or Navigational Telex is a global maritime communication system that provides navigational and meteorological warnings and urgent marine safety information to ships at sea.

NavTex works by aggregating navigational reports into a central broadcasting station and sending it simultaneously to ships within the vicinity.

It is a crucial tool for enhancing maritime safety by delivering essential information to vessels, helping them navigate safely and avoid potential hazards.

17. Navigational Lights

All ships must exhibit the correct navigational lights prescribed in the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS).

This colored lighting scheme is displayed at night and in restricted visibility to indicate a vessel’s presence, type, activity, and heading with respect to your ship.

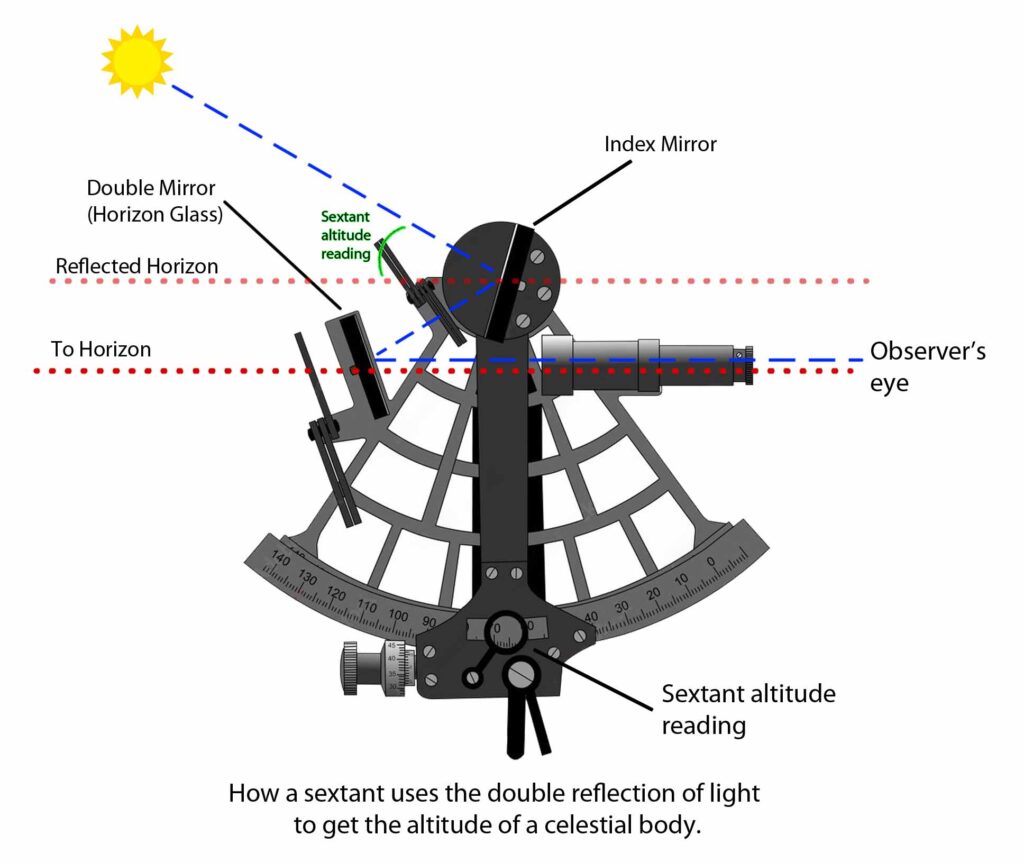

18. Marine Sextant

Many of the outlined items rely heavily on electrical power, particularly the critical ones.

In the event of a failure in these electronic navigational devices, the marine sextant emerges as a crucial tool to prevent seafarers from losing their way. Consider this a traditional backup and skill.

Its principal objective is to ascertain the altitude or elevation of celestial bodies above the horizon. Using trigonometry and tables called almanacs, the mariner can calculate the ship’s latitude and, in some cases, longitude.

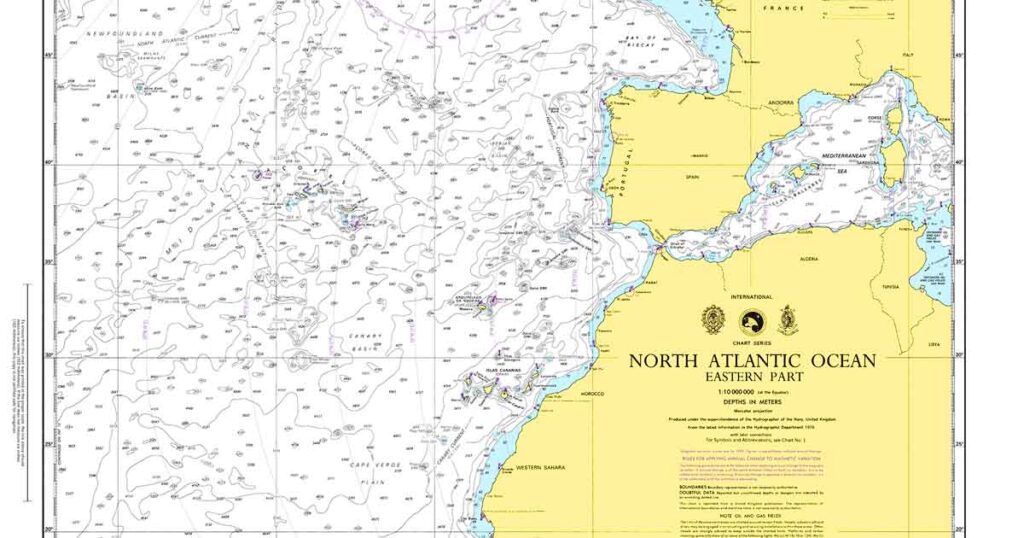

19. Nautical Charts

While vessels widely use electronic charts, you can still find a few paper charts on board.

These nautical charts are usually large scale general charts that cover huge sea areas and work in tandem with the marine sextant.

After doing your sight and calculations, you can plot your position on one of these charts, so even if your electronic devices fail, you still have these navigational tools to find your way.

20. Binoculars

No matter how advanced our ship’s navigational devices may be, binoculars will always be a part of our seafaring lives.

Binoculars are magnifying portable optics that aid visual observation over distance.

They are useful for lookout duties like sighting lighthouses, buoys, and shorelines. It also assists with collision avoidance via improved visual scanning.

21. Pelorus

Also known as a dumb compass, a Pelorus is a navigational instrument mounted on the ship’s compass for taking relative bearings to maritime landmarks, navigational aids, and other vessels.

They can be extremely useful for cross-bearing and are actually one of my favorite position-fixing tools before the age of electronics.

22. Daylight Signaling Lamp

Portable electric signaling light using Morse Code flashes. Allows communication with shore stations, ships, aircraft, and survivors at distances up to several miles in the day and nighttime.

It is also used to get the attention of another vessel if they don’t respond after being called on the VHF radios.

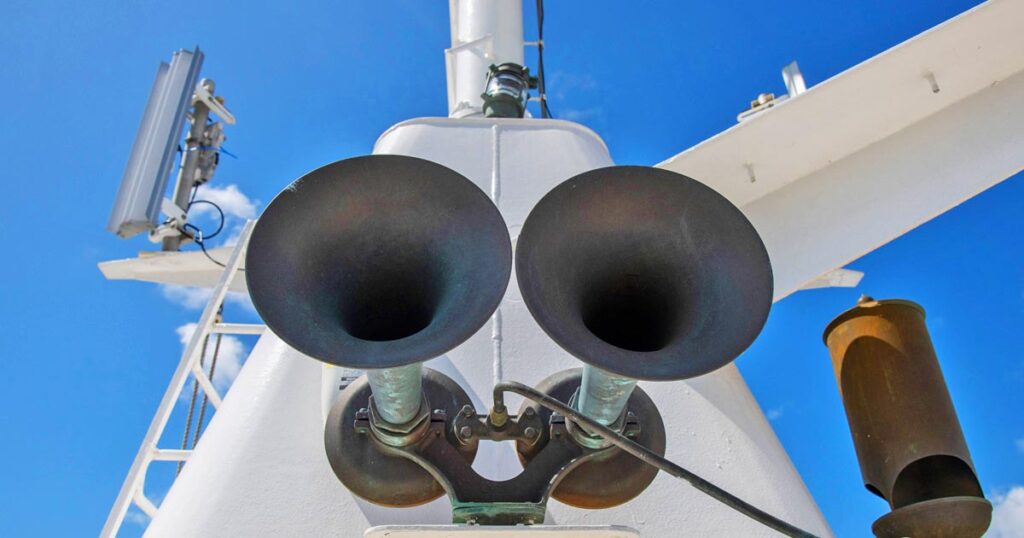

23. Ship’s Whistle/ Fog Horn

Used to signal course changes, warnings, and other navigational and operational intentions via standardized whistle-blast sequences. Audible signals assist in collision avoidance.

They are a requirement in COLREGS, and you can use Morse Code to signal to another ship.

You can find two onboard- atop the monkey island and the forward mast.

24. Forecastle Bell

Traditional bell located on a ship’s foremast and can either be rung by hand or automatically in specific patterns to indicate time, emergency maneuvers, or other events.

The forecastle bell is used during restricted visibility to indicate the presence of your vessel.

25. Navigational Shapes

Lights, shapes, and sound signals are very important on vessels.

While we have navigational lights at night, we also have shapes used in the daytime that signal specific conditions about our vessel to aid in collision avoidance.

As a requirement in COLREGS, these standardized shapes are usually colored in black. They are displayed to convey a vessel’s status, such as anchored, aground, not under command, restricted maneuverability, etc., to other ships.

26. Flag Signals

System of signal flags hoisted in specific orders to communicate messages between ships and shore when within sight.

In the maritime world, each letter in the alphabet has its own flag. The flags can be combined to indicate specific meaning and intention to other vessels.

Conclusion:

In closing, while modern navigational systems and automation continue to develop rapidly, a solid grasp of traditional principles remains invaluable for all mariners.

Technologies can and do fail, often unexpectedly. An experienced navigator must stay adept with fundamental tools like the magnetic compass, sextant, and paper charts to ensure safe passage regardless of conditions.

Just as crucial is understanding the technical intricacies and limitations of advanced systems. Maritime navigation demands both art and science – the blend of age-old skills and new-age gadgetry.

As long as people sail the seas, this timeless wisdom will hold true, guiding ships safely on their voyages.

May the winds be in your favor.

0 Comments